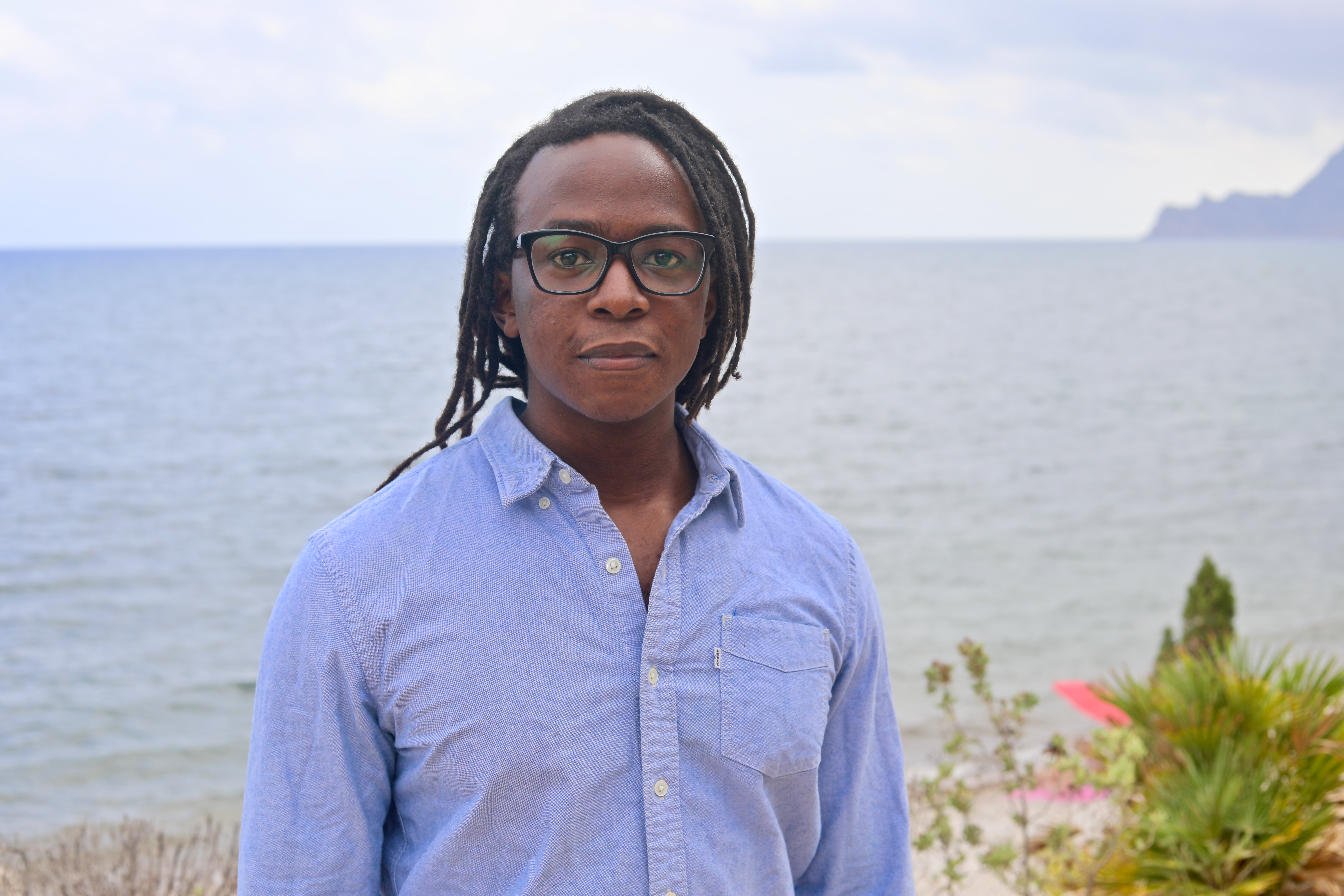

Interview: Gibbs Kuguru, Shark Geneticist

Posted by Esther Jacobs on February 4, 2019

Gibbs Kuguru is a molecular geneticist and his studies primarily focus on the population dynamics of smooth hammerhead sharks. Gibbs spent six years researching sharks with White Shark Africa, a white shark cage diving company in Mossel Bay, in tandem with Stellenbosch University. Our director of research, Dr Enrico Gennari, was one of the supervisors for his research.

How does genetic research tie in with conservation, for hammerhead sharks?

As a charismatic species, little is known about the populations of smooth hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna zygaena).

By using genetic tools, I can determine the fitness of populations and also how inter-connected they are… all this information comes from a tiny piece of tissue that I source from these sharks.

Ultimately, I hope to share my research with fisheries management bodies so they can be informed on how to better conserve hammerhead shark populations.

Did you make any interesting discoveries about the species during your research?

I would consider the presence of sibling relationships, within the hammerhead shark populations I sampled in Mossel Bay, to be the most interesting finding.

Most of the hammerheads I found in the field were either juvenile or newborn, as indicated by the presence of umbilical scars. When I analysed their DNA, I found a majority of the sharks shared the same mother, and some even shared the same mother and father!

This strong familial presence could either buffer or amplify the negative effects of overfishing and the environmental permutations associated with climate change. Either way, we should take every step to restore the health our environment.

What were the challenges of working with hammerhead sharks?

Hammerhead sharks are highly sensitive to the activities around tagging and tissue sampling.

This meant that we had to be hyper-vigilant when handling the sharks because the likelihood of post-release mortality is high among these species.

Even after they are released and swim off, they are at risk of dying from stresses associated with a physiological response to capture.

What are your main goals for research and conservation, now that you have returned to Kenya?

I hope to fill the gaps in data when it comes to chondrichthyan research in Kenya.

The Western Indian Ocean (WIO) has a high diversity of chondrichthyans, with limited data available on their distribution and abundance. This, paired with poor management, has led to steep declines in the abundance of many shark and ray species. It has been considered that some species, like the sawfish, have experienced regional extinctions.

Therefore, it’s important that we understand the extent of this predicament. I will be working with consortia like the UN Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment, to find scalable solutions to these complex problems.

What are the main differences between Kenya and South Africa regarding working in conservation?

In my opinion, conservation initiatives are primarily driven by the public sector in Kenya and by the private sector in South Africa.

Though the motivations behind conservation are quite similar for both countries, ownership of the solutions are held by the people in South Africa and not by the government.

Neither system is perfect, but I find the one that fosters stewardship among the people and communities will ultimately last longer and be more effective, i.e. private sector.

Name three actions a conservationist could do in an African country, to really make a difference in shark conservation?

Here’s my proposal…it’s really one action with three steps, when purchasing seafood:

1. Is the location of where your seafood was sourced known?

2. Is that type of seafood caught sustainably?

3. If you can answer both of those questions with a “yes”, then you can make that purchase.

Given this, I also believe that contemplating your food is less important than actually eating it after it’s been harvested.

Photo: Lilian van Kesteren